#I remember when the move from shooting on film transitioned into digital

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

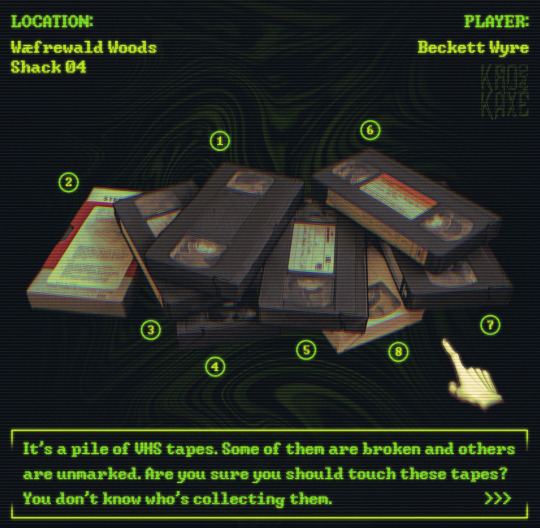

It's a pile of VHS tapes. Some of them are broken and others are unmarked. Are you sure you should touch these tapes? You don't know who's collecting them

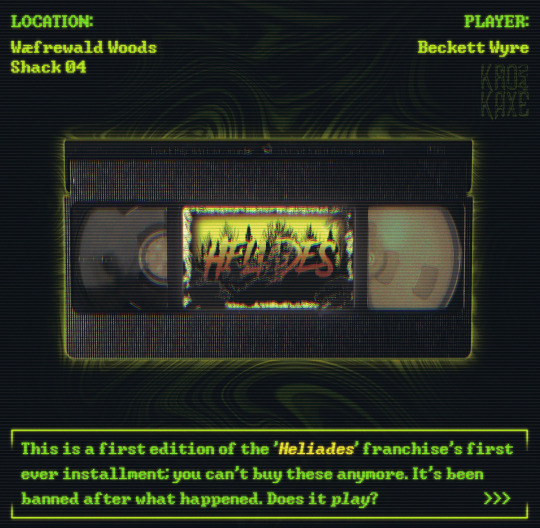

This is a first edition of the Heliades franchise's first ever installment; you can't buy these anymore. It's been banned after what happened. Does it play?

#krok.png#Horror#Concept Art#Fake Screenshot#Game Concept Art#Point and Click#Horror Games#OC: Beckett#VHS tapes live in a very special part of my heart#Aged media formats I love you#Digital behated (irony)#I remember when the move from shooting on film transitioned into digital#give us BACK the film grain#Arcadia#Skeinridge#The Conduit Tapes

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Justice Mukheli On Telling Authentic African Stories Through Art

Justice Mukheli is a film director, photographer, and artist. Through his visual storytelling, he takes viewers through a journey of African stories that embody truth, power, and beauty. He documents everyday South African experiences through his lens which makes his art feel like home. It is evident that Justice Mukheli is rooted in his heritage as he draws inspiration from his upbringing in Soweto to enrich his work. Whether he is capturing on film or digital – his photography is full of soul, which can be seen through the eyes of his subjects. Art becomes a conduit for Mukheli to heal, breathing life into untold stories and contribute towards moving the African culture forward.

From working as an Art Director at Draft FCB to being a Commercial Director for Romance Films TV, how Justice Mukheli has constantly elevated himself through a plethora of creative mediums is truly inspiring. During our catchup in Rosebank over coffee, I learned more about his journey from advertising to art, how he achieved his tremendous success as well as his new path of being appointed the Commercial Director at one of the best production companies in the world, Romance Films TV.

1. How did growing up in Soweto inspire your vision of storytelling?

Growing up in Soweto inspired me in a lot of ways that are beyond the storyteller I thought I would become. The way we grew up and being a child at the time, Soweto was amazing. There was a freedom that kids don’t have – now that my life is this side of the world. Maybe on a weekend, I would just wake up and leave the house at 7 o’clock and go explore with my friends, come back before the sunsets. And it would be either from going to catch locust in the bush or creating our soccer field somewhere in the bush corner or playing under tunnels. We used to get under tunnels and walk. For example, we would get into a tunnel here, go through the tunnel, and get out in Bryanston. They were like a maze. There were so many activities as a kid. My childhood was amazing with memories and my parents were amazing. I was very close to my dad for the time he spent with us, close to my mum. She used to bake, we used to help her bake and knit. There was so much available to entertain me as a kid growing up in Soweto. There were these older gentlemen, friends of my uncles who dressed up incredibly beautiful and you grow up seeing that and aspiring to that. The car culture, sneaker culture, fashion culture – there was just so much.

2. What are some of the unforgettable childhood experiences you believe shaped who you are today?

When I get work or need to do or tell a story, I have a huge bank of resources and stories to borrow from, to look back into. I become excited about how I can bring those lived experiences into life, into the story I was trying to get. As a commercials director, when I get a brief most of the time, I look back there in my bank of memories. Have I experienced something like this? My latest commercial is about a funeral plan – this old man leaving his last message to his wife. So when I got briefed, it became immediately clear to me that I have experienced this. The point of view might have been different because I was a child but I can remember all those moments when my grandmother lost my grandfather and what happened and the nuance in how she was and how she dealt with the nuance of my culture and how we deal with loss. That was a huge and most incredible resource to go look into as a source of inspiration and borrow from. To breathe that experience into that piece so that it feels authentic. As a filmmaker and artist, we recreate moments and it’s in how close to reality we get. That’s my tool. It’s what I use all the time.

3. You recently joined Romance Films TV as a commercials director. How do you feel about this new path?

I am beyond excited about it. I wrote on my Instagram post that I have been inspired by Romance Films TV before I even thought that I would be a filmmaker. From 2009, when I got into advertising, I remember they would say to us when you write your advert you must write it for Grey Gray to take your script, to even consider shooting your ads for you. Grey Gray is a founding partner for Romance Films TV. He is incredible. He is an incredible storyteller. We used to write these ads and send them to their company. We would cross fingers that he considers our script. Unfortunately, when I was still in advertising I never got to work with him. Maybe our scripts were not good enough. It is exciting that the loop closed. I am excited to learn from them. There is Terence Neale who is incredible, he works mostly internationally. His ads are breathtaking, such as the ad he did for Beats by Dre. I have known them and had a friendship with them for a long time. It feels right to have joined them now because I have gained my own experience. I have scrabbled, built myself and built my confidence. I have proved that I can be a filmmaker. Now it’s amazing that I am part of a team that I have reached to be a part of for the longest time.

4. From working as an Art Director to being a Commercial Director, how did you navigate the transition from advertising to art and how did you own that space?

The transition was relatively easy. And I say this because advertising is an incredible teacher. Marketing teaches you how business works, positioning, and what you need to do to get a product to a certain target audience. I saw myself as a product when I started my journey as a photographer. Like okay cool, I’m a photographer. How do I get myself seen by those I want to book me? I had to build a portfolio using knowledge from advertising. I was in advertising for 7 years before I transitioned. My understanding of the industry helped my transition work seamlessly because I knew what to do. I knew the power of a portfolio, I knew how to get myself in front of the target audience that I need to book me. Owning the space was putting in the work and understanding what is needed to get myself to a position where I am considered or seen as someone interesting in my field or someone who has a different point of view or a different way of doing things. That is part of owning the space and creating work that is unapologetically my voice. And in the same vain, answering the client’s brief and aligning the brand with its target audience. And aligning the brand where marketers intend to get to. I make sure that my work is an extension of what my clients need. As a film director, I am a part of the chain.

Your voice is your own lived experience. For example, when I got briefed on Hollard, there were 2 other directors. There were 3 of us. It’s always important that I borrow from my lived experiences because it will be a unique point of view, a unique point of departure. After all, all the other directors will also come from their point of view, understanding, or lived experiences. That’s how they work and when I present my treatment it will unapologetically be me. It will have my voice, tone, and feels. With Hollard, the way I saw and experienced my grandmother grieve for my grandfather is unique to me. So I reconstructed and rebuilt that world from how I saw it.

5. In terms of your photography, what qualities must a subject have for it to be captivating enough for you to capture it?

For me, it’s not about aesthetic qualities, it’s about the feeling I get from the eyes. It’s not an aesthetic thing. It’s mostly eyes and the feeling that I am trying to capture. My creative process is led by feeling rather than an idea. The idea is secondary to me. For me, the important thing is how does it make me feel. I have always felt that advertising teaches us that “idea is king” and I agree. But for me, the feeling is more important than an idea because you can get an idea but it doesn’t move you. The feeling is more important to me. Sometimes I use to gravitate towards kids a lot because it was a process for me to unpack my other lived experiences - emotions I never got to deal with acknowledge or immerse myself in. Sometimes when we go through what we go through, we are not present enough to go through the emotions of it and deal with it. Photography and film have become a tool I use as therapy for myself. I can tap back into a moment that is important to me and I deal with it, and I can capture that feeling.

6. In your tremendous career, which would you say are your favorite works that you have produced and why?

I love the Ingrams advert and the Hollard advert. There is an advert I have created for South African Tourism, it has a slightly different tone than the ads I am creating now. It was about portraying black people experiencing their land on these spaces that are mostly enjoyed by white people but enjoying them their way. I quite like the advert.

7. The advertising industry in South Africa has transformed in terms of how black culture is represented, however so much work still needs to be done to move the culture forward. What do you think agencies can do better in this space?

Agencies still fall into the mistake of not being mindful of black stories by black people, or at least having black collaborators in the chain of those stories being told. I think the industry very quickly falls into thinking that “ALL LIVES MATTER” type of mentality, that creative is creative. “What makes you think that just because I am a white person I won’t be able to tell a story in a sensitive way?”. I don’t think that’s the conversation. I think the conversation is telling the story most authentically and mindfully. I think advertising needs to create space for black narratives to be inclusive of black people from the process of creating it.

8. If you ever feel a creative block during a project, how do you reconnect and channel your energy?

I have a lot of creative resources and creative outlets. If my photography is struggling, I am going to paint. Now, I have decided that I want to paint again because I am not so inspired photographically. I am going to start to paint more. If directing or my other outlets are struggling, I can make music or I can sculpt, or I can write. I have a lot of outlets.

9. Which creative materials inspired you on your overall journey? It could be a film, book, exhibition, documentary, or anything?

It was a book by Malcolm Gladwell called Outliers. It speaks of the 10 000 hours rule and it touches on the people who are amazing that we love and follow. The people who inspire us decided to put in the work, it didn’t happen by chance. That book taught me that whatever I want to be, I can be. I can make that happen, no one else. And it can never happen by mistake.

10. Which brands and artists would you like to collaborate with in the future?

I would love to work with Netflix. And in terms of artists, there is an artist I like called Sibusile Xaba. He’s really amazing. That’s who I would love to collaborate with.

11. And lastly, which words of advice would you give to young artists who aspire to manifest their dreams in this multifaceted creative industry?

My last words would be what I just said about what I got from the book, Outliers – what you want to be, only you can make happen. Great people are not just great by mistake. It just doesn’t happen to them. It was a choice. If you want to be amazing at something, you need to decide to be. It’s a process, it won’t happen overnight.

Image sources: https://www.justicemukheli.com/work Justice Mukheli Films: https://www.romancefilms.tv/directors/justice-mukheli

#SOUTHAFRICANART#thelifedocumentor#Zesintu Mgobhozi#lifestylebloger#African photographers#african art#justice mukheli

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

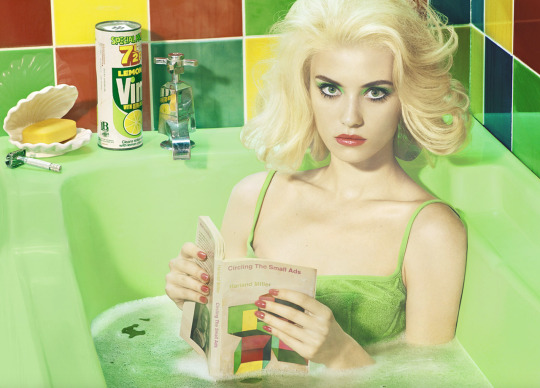

The second of a two part Miles Aldridge interview I did for the Image Source Picture Agency. Here, the avant-garde fashion photographer talks about the transition to a different creative vision, and the contrasting influences of Richard Avedon and Helmut Newton.

Ashley Jouhar: The transition you made to the kind of work that we associate with you as a photographer now… how did you go about creating that imagery?

Miles Aldridge: Well as an example, I had this idea for a photograph that took place in a car, with the exhaust coming through a window. That could still work as a photo. I wanted to do a series like that but what other ideas could I come up with? I went through the other ideas and they were all to do with suicide! That’s how it started to happen.

The people I worked with were very accommodating, especially Italian Vogue. I’d done white background shoots for them for quite a while. So when I proposed to do something with a bit of narrative to it, as along as I shot their clothes they were fine with it. Actually, those pictures turned out quite well – they emboldened me to do another one and another one.

Some of the early stories aren’t much of a story but there is still a story there because something is happening. I remember one where I just wanted to have a white kitten in every picture. Following this girl around the street loosely inspired by this girl from La Dolce Vita. That was a case of making sure there was a white kitten on set and just making sure it was in every picture.

Ashley Jouhar: How long does it take now to make an individual image and what’s the size of the team involved?

Miles Aldridge: The team is the same now, it’s a bit like a Rock ’n’ Roll band. Instead of the drummer, the bass player and guitarist, you have the stylist, hair-dresser and make-up artist, the set designer and the prop stylist. It is like a small art movie team – it’s not Hollywood. It’s a group rather than a massive bunch of people. I try to keep control of it, keep costs down. So it doesn’t becoming exorbitantly expensive. As long as my drawings are quite accurate from the beginning, I don’t have to make huge sets, I just make the bit I really need.

Typically I’ll have an idea and I’ll sell the idea to the magazine. Within that six months we’ll shoot it as an idea, over two days mostly – sometimes over one day. Now half the shoots are one day shoots.

Ashley Jouhar: Is it mostly sets you shoot in rather than locations?

Miles Aldridge: It goes up and down, I go through different phases, sometimes I like shooting in locations as I find locations give you a lot more options once you are there. They exist in architectural space. If the idea you had thought of doesn’t work, you can probably move the camera and find something else that does work. Whereas a set has no Plan B. You are pretty much figuring out your shot when you are doing a drawing and have the set constructed accordingly. It’s quite nice going into a location like a hotel room and taking it over changing it and putting lights up and really doing a number on it. Changing it through the camera, though the lighting, and propping. I’m quite happy in a studio as a set as well.

When you have a free rein, and it sounds like a lot of the time you have, it can be more difficult to create, as the world’s your oyster. How do you impose your own parameters to get to be where you want to be?

Because I work for Italian Vogue the parameters are not defined but are well understood. You can do a picture of a crazy woman but it does have to be tasteful, it can be contemporary so it can include knowledge of contemporary art but I think it can’t be shocking for its own sake and it can’t trample over certain taboos.

There’s a restriction there and of course you have to show the clothes. And I’m also obliged to make sure that the woman looks really beautiful even if she is weird. There are enough parameters there to make it interesting. I agree though, when artists are given free rein, they often produce rubbish. I like to consider myself working in a similar way to the Hollywood writers and directors in the 1940s and 50s… Celebrating that and everything in between.

Ashley Jouhar: When we were talking at your show Short Breaths, about film versus digital, you were saying you do some commercial jobs on digital but mostly you are shooting on film to get the qualities it provides. For shoots for Italian Vogue for instance, would that be film?

Miles Aldridge: Absolutely. All the work in Short Breaths and all the work in Somerset House was previously published in magazines and ninety percent of that was Italian Vogue. For me, the personal work is the magazine work – I consider that my art, in the same that Richard Avedon and Helmut Newton did too. I don’t consider that commercial work even though it’s for a magazine. What I consider commercial work is pure advertising, where it’s a product for a company who want me to show their things. You have to work with someone else’s brief in advertising. Historically, editorial photographers are reporting on the world. They are aware of fashions and the world they live in so the ideas they have and the images they come up with are not just to show the clothes – that would be deadly. The job of the fashion photographer is to subtly make comment on the world he lives in.

Ashley Jouhar: Which fashion photographers have influenced you? Whose work do you like the most?

Miles Aldridge: I think as far as being incredibly serious about what he did – and he straddled such a huge period of human culture and commented on it, it would be Richard Avedon. Helmut Newton is also a very interesting and prolific artist who did the same for a more concentrated period in the 70s and 80s. He did in the 60s too but came into his own in the 70s. He was such a pervy, dark guy but I think that vision suited that world of the 70s. Both of these artists are true to their own nature. There is something about Avedon and his obsession with grace and glamour but he was massively aware of the world he was in, the Berlin Wall coming down, the rights of Black people, or the American West project being a shocking report on one of the world’s richest countries.

Ashley Jouhar: He was heavily criticised at the time for some of these images. But look how influential they’ve been.

Miles Aldridge: Irving Penn is another one. He is less a fashion photographer than a still life one. In his way, he has an incredible breadth to his work, a huge span of human existence that’s fantastic.

Ashley Jouhar: I saw the Platinum Cigarette Butts show at Hamilton’s last year – phenomenal to see them all together…

Miles Aldridge: Wonderful…

Ashley Jouhar: And again very influential…

Miles Aldridge: Like a lot of great work, if the idea is great you can get the cigarette butt out of the gutter and put it under a camera. He followed it through technically and did it brilliantly, but for me the brilliant bit of that is the idea. He said, walking home from the studio, he would pick up these little bits of detritus and bring them back to the studio the next day to photograph. It’s the idea to do that that’s the amazing thing.

Ashley Jouhar: It’s easy to look back at stuff like that and say, well… that’s an old idea but of course, at the time it was breaking new boundaries…

Miles Aldridge: And in its own way it was talking about consumerism.

Ashley Jouhar: One more question. Your current body of work has an ‘energy’ and a ‘Miles Aldridge’ look and feel. Is anything hatching in your mind as to how you are going to move it on? Where are you going to go next with your style or approach to image-making?

Miles Aldridge: The exhibition and the book are both incredible full-stops for me – a double full-stop. I feel the new work after this, starting in September, will be different. What I am doing right now is really considering that. I feel the body of work at Somerset House is a really complete representation of how I felt about the world up until now. Now that’s off my chest it leaves room for me to think again and see things in a different way.

Ashley Jouhar: Thank you very much Miles.

#fashion photography#fashion#art photography#pop art#ashleyjouhar#miles aldridge#british vogue#vogue italia

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

GRETA GERWIG TALKS TO FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA

Excerpts from Interview Magazine November 2, 2017.

COPPOLA: Let’s start at the beginning: When did you stop believing in Santa Claus?

GERWIG: I got an easel for Christmas—I think I was 7 or 8—and the easel had “Merry Christmas” written on it in all these different colors, and I recognized my mother’s handwriting. I said, “That’s not from Santa Claus. I know that’s your handwriting.” And then I proceeded to do a dance around the living room saying, “I figured it out, I figured it out.” And while I was doing that, I started weeping because I thought that meant there was no more magic in the world. That story actually says a lot about who I am now. I get this pleasure in figuring things out, and then it turns into complete despair.

COPPOLA: Did they own up to it when you discovered the truth?

GERWIG: They did, because they thought I enjoyed it and didn’t realize I was going to turn so quickly. I had a similar thing with movies. I thought movies were handed down by God. I knew that theater was made by people because I saw the people in front of me, but movies seemed like they were delivered, wholly made, from Zeus’s head or something.

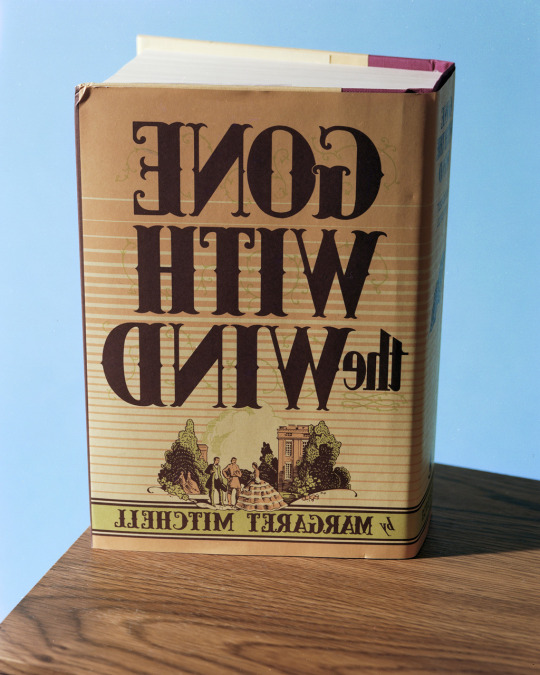

COPPOLA: As a kid, were you a big reader?

GERWIG: Yes. Books and theater were the way I understood the world, and also the way I organized my sense of morality, of how to live a good life. I would read all night. My mom would come into my room and tell me I had to go to sleep, so I would hide books under my bed. At first I had a tough time getting through novels, so I read plays, because a play is generally shorter and has all those tools for getting people hooked early on.

COPPOLA: What was the first play you can remember reading?

GERWIG: I remember reading a lot of Eugene O’Neill and Arthur Miller, and being so impressed by Miller’s stage directions. He included very detailed descriptions of how the set is supposed to look, and that allowed me to be inside the plays even if there wasn’t a production going on. In terms of sheer pleasure, Tom Stoppard was very big for me because he is so funny and so smart, and it felt delicious reading him. I got it in my head that there was no way I could ever make plays because you would have to be so incredibly smart, and I was not going to be as smart as those people.

COPPOLA: What was it like making the transition from your early films—when you were practically in college—to these more established ones?

GERWIG: I wanted to be a playwright in college. That’s what I was interested in and that’s what I was moving toward, and then I had the very lucky accident of falling in love with film. Like we were saying, it wasn’t until I was 19 or 20 that I realized films are made by people, and I had the good luck of suddenly meeting them. Shooting digitally became cheaper and better. Editing became something you could do at home. You couldn’t make something that looked like a Hollywood film, but you could make something through which you could work out ideas. I was acting, but I was also conceiving the plots and operating the camera when I wasn’t onscreen or holding the boom and sitting there at night looking at how it would be edited together. In a way, I got very unvain about film acting, and it became a sort of graduate school for me. At the same time, I was busy getting rejected from every real graduate school I wanted to go to for playwriting. [laughs]

COPPOLA: ...when I lived on Long Island I wanted so badly to live in New Orleans. And then years later I did go to the French Quarter—it’s a wonderful place to visit—and I thought that I was going to write plays and have a girlfriend and all of the things that I wasn’t having, but I didn’t.

GERWIG: I once went through a major Sam Shepard phase, and I thought, “I’m completely in the wrong place, and I’m the wrong gender! And I’m also not a heavy drinker! And I need to somehow become a wild man and go out to the West and learn how to rope cattle!”

COPPOLA: I don’t think Sam Shepard knew how to rope cattle.

GERWIG: Well, he seemed like he did! I think the problem with growing up and idealizing self-destructive artists is that you only see the beauty they created rather than all the pain that went along with it. But then I read Joan Didion, and it was the first time I’d read something by an artist—a great artist—who was working in the same place I was from and writing about it, and it was the first inkling I had that maybe I didn’t need to be a different person in order to make something that was worth anything.

COPPOLA: That’s what your film is about, isn’t it?

GERWIG: I guess it’s a revelation I’m still dealing with.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Life in Film: Michael Tyburski.

The Sound of Silence director Michael Tyburski shares some insights into the making of his debut feature, and answers our new “life in film” questionnaire.

In The Sound of Silence, Peter Sarsgaard is Peter Lucian, a house tuner in New York City who believes that the notes emitted from a household’s appliances must harmonize in order to bring peace to its residents. However, his state of mind collapses when he struggles to apply his methods for a new client, Ellen (Rashida Jones).

Directed by Michael Tyburski and based on a short film he made with co-writer Ben Nabors in 2013, The Sound of Silence debuted at the Sundance Film Festival and stood out for its “remarkably silly” unique premise and strong performance from Sarsgaard. Fans of ASMR, get your headphones out; the film’s sound design will trigger those sensations.

The Sound of Silence started life as your short film Palimpsest. Is the ‘house tuner’ occupation at all based in reality? Michael Tyburski: The short answer is no, it’s a fictional profession. The character idea is something that my co-writer Ben Nabors brought to me. Right away, I loved the idea of a practise where someone shows up at your door and offers you a solution to the emotional problems that you’re having.

A lot of alternative therapies exist in New York City so it didn’t seem so far from reality that people would take someone intellectual, dressed well in a tweed blazer, with professional-looking tools, seriously. I really liked that as a conceit. We tried to base it in real science and looked at sound engineers and acousticians for what tools they would use. We tried to make it exist in a very real New York City; that’s why we have touchstones like the character being profiled in The New Yorker.

How has your research into music theory affected your own domestic space? Actually, I moved, for the first time in ten years—after living on a pretty noisy commercial street—during the course of developing and making this movie. Somehow, during the edit, I made my first apartment move within New York City, to a much quieter street. I also took a cue from the main character, Peter Lucian, because I moved my office below my apartment, in a subterranean space. At least I can control the sound a little bit more now that I’m cut off from the surface level, similar to the way Peter does it in his “fallout shelter”.

Michael Tyburski and Peter Sarsgaard on the set of The Sound of Silence. / Photo: James Chororos

The character Peter Lucian feels like a perfect fit for Peter Sarsgaard. When did you have him in mind? He was my first pick. I knew I wanted him from the beginning when I first started thinking about who would be the perfect house tuner. I feel so lucky to have him and fortunately the script resonated with him right away. He’s someone who’s very musically inclined and he plays a number of musical instruments. I was so gratified that he connected to the part so closely.

He’s such a chameleon of an actor. He can play a lot of dark roles, but also he has a very scientist-like intellect. I also think he has one of the best voices, it’s very unique and I enjoy hearing him. So for a movie about sound, it kind of seemed fitting that someone with those types of qualities would work for the role.

What was important to you about keeping Peter’s house-tuning technology analog instead of digital? I think he’s just someone who has the philosophy of “if it’s not broke, don’t fix it”. Even though his tools are a little more dated, they’re still as effective. They might not be as efficient as digital technology so he’s a little slower, but they still work. There is at least one sound engineer in New York City who we found in our research who measures the sound in rooms, and there’s one thing called a spectrum analyzer that we use in the film that we completely got from this guy’s tool bag.

Director Michael Tyburski.

The film is carefully crafted and you have Peter obsessing over every inch of New York City. What degree of obsession did you have in the making of the film? I’m pretty obsessive as an individual in general. I like to be very organized and have everything mapped out. We had been developing the screenplay for so many years that I got tired of reading it, so before we made the movie, the first thing I did after Peter came on board was sit down and record the entire script in audio format. I kind of had this radio edit of the movie. That transitioned into a rough animatic of the film that I put into the timeline and I was able to add in location references, tonal reference photos, dialogue in different room tones, and then music.

Logistics-wise, we only had 21 days to shoot the movie which is very conservative especially because we had a lot of ground to cover, but I just needed to be as efficient as possible, so it was helpful to have that thorough, animatic tool.

With all the technical departments it was a very close collaboration and I like to be very involved in all details. For the sound design, I wanted to re-record all of the tuning forks, which were kind of an aural motif through the film. When you’re shooting in the elements, you don’t always have the control over the environment, so I hand-recorded each one of the tuning forks myself. We were aiming for that level of precision.

We’d like to ask a few questions about your life in film. What was the film that made you want to become a filmmaker? My choice is probably not that unique but when I was 13, maybe a little too young, I got a VHS copy of Pulp Fiction. That stunned me and took me from A to B. It shook up how I thought contemporary American stories could be told.

Which film do you think is the best love letter to New York? Annie Hall, closely tied with Midnight Cowboy. I suppose I love that era of New York.

Which film has the greatest sound design work of all time? There’s a lot, but one of my favorites is Play Time.

Nice choice. Greatest production design of all-time too. Yeah, not bad. I used a few frames for my look book.

Jacques Tati’s ‘PlayTime’ (1967).

Which is the most overlooked performance from Peter Sarsgaard? I loved him in Experimenter, which I think is an underrated film. More recently too, Errol Morris’s Wormwood. I don’t know how many people went down that rabbit hole because it was long, but I think he was so good in it.

What films did you watch to prepare you for The Sound of Silence? There were three that we were looking at, for a lot of different reasons. We watched Jonathan Glazer’s Birth for the mood and that fairytale vibe it has in a mysterious, alternate New York City.

Being John Malkovich for its bizarro version of science, and I love the naturalistic quality to that film. And obviously The Conversation for its production design and how it follows a man obsessed with sound.

This is a nicely-timed, autumnal, gentle film. What films give you those peaceful autumn vibes? My favorite is Hannah and Her Sisters.

What mindfuck movie changed you for life? I’ll have a couple Kubrick on this list, but for this probably A Clockwork Orange.

It’s Halloween next month. What movie do you watch every Halloween? The Shining! There’s my next Kubrick.

As a teenager, what film character felt like a total mirror to what you were feeling at the time? One of my favorite coming-of-age films is Harold and Maude. I definitely identified with Harold.

What’s your go-to comfort movie? And how many times do you think you’ve seen it? My favorite film of all time, which I promise will be my last Kubrick, is Barry Lyndon. I think it’s just a perfect movie and I’ve certainly seen it dozens of times. I think it does everything I want in a movie. I don’t even know what genre to call it because it’s funny, it’s dramatic, it’s an epic. I love the idea of doing a perfect epic movie that covers a lot of ground.

Stanley Kubrick’s ‘Barry Lyndon’ (1975).

What film do you have fond memories of watching with your parents? We were a big Chevy Chase household and National Lampoon’s Vacation holds up as a fine movie.

What’s a classic you could just not get into? Maybe Brazil. Admittedly I think I need to rewatch it because I first saw it when I was 14 or 15 and I just didn’t quite get it at the time.

What classic are you embarrassed to say you haven’t seen? Two Kurosawa films; Rashomon and Seven Samurai. They’re always on my list to brush up and they seem to come up in conversation more and more.

Which movie scene makes you cry the most? Definitely the holiday classic It’s A Wonderful Life.

What film was your entry point into non-English language cinema? That was a good one, I like that question. I remember when I was in my freshman year of high school I was given two VHS copies from someone who knew I was getting into film. One of those films was Persona, but then the other one, which I knew I watched first, was a film called Woman in the Dunes.

What filmmaker—living or dead—do you envy the most? If Kubrick, go for living… If it’s Kubrick go for living? Oh my gosh.

I feel like you’re going to say Kubrick. Yeah. Envy is a funny word. Kubrick has an admirable career for the depth of his filmography. You know, like a lot of film nerds I’m a huge Paul Thomas Anderson fan.

Christopher Nolan’s ‘The Prestige’ (2006).

What’s a film that you wish you made? I would love to make a movie about magic but ever since I saw The Prestige I think it would be hard to compete with that. That period, that Victorian era of illusion, I don’t know if you can top that.

It’s time for best-of-decade lists. What’s the greatest film of the 2010s? If we went back even further it would be easier. For the last 10 years, I think Phantom Thread is pretty great.

‘The Sound of Silence’ was released on September 13 by IFC Films and is in select cinemas now.

#the sound of silence#michael tyburski#peter sarsgaard#new york#kubrick#filmmaker#director#best of#letterboxd

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Get to know me tag

I got tagged by @havokhayley so go blame her for me shit posting 😘

Rules: Tag 10 followers you’d like to get to know better!

Name: Edie

Birth Year: 83

Sign: I’m a (third generation) cuspian, so I’m Cancer/Leo. Does that explain everything about me? Kind of.

Height: 160 cms, so 5ft 2.

Put your playlist on shuffle and name the first 4 songs:

Playdate - CBX We Go Up - NCT Dream Sunshine - Hoody One and Only - EXO This is terrible representation. I usually skip 1&Only. I’m so not a ballarder. I have one Nct Dream song in a giant kpop playlist and it comes up?! Honestly. Also, I have multiple kpop/sweet teeth related playlists which some of the anons have access to so hit me up if you want a link (only to known anons/mutals soz)

Grab the nearest book, turn to page 23. What’s the 17th line?

“But the most immediate predecessors of digital games were carnival games... (throwing a ball at a stack of bottles from a set distance), mechanical games (a shooting gallery with moving targets), and pinball machines.” -Chapter 2: The History of Magic from Rise of the Videogame Zinesters: How Freaks, Normals, Amateurs, Artists, Dreamers, Dropouts, Queers, Housewives, and People Like You Are Taking Back an Art Form” by Anna Anthrophy (2012).

Ever had a song or poem written about you?

Not that I know of. Perhaps my mother wrote a poem once or twice. She writes lovely poetry.

When was the last time you played air guitar?

A long time, I honestly can’t remember. I play air drums a lot though, and lip sync almost constantly whilst listening to music in transit.

Celebrity crush(es)?

Perhaps you’ve heard of them?

What’s a sound you hate/love?

Hate: Breaking bones. Love: I’ve said it before but female orgasms. God damn.

Do you believe in Ghosts?

Yeah, why not?

Do you believe in Aliens?

Yeah, why not?

Do you drive? If so, have you ever crashed?

Can drive, don’t drive, have crashed.

Being an Australian means you have a very specific relationship with driving and cars, but I was raised by two people who love cars so I was driving at an early age. The first car I ever knew was my parent’s pride and joy - a silver Porsche 911. My first car was a Datsun, and I have incredibly sentimental memories of the cars of my youth - especially one of my boyfriend’s - a red 1970s-80′s GT Celica... you can guarantee that if I write a fic with a car in it (like Sehun’s), I’m probably imagining the bonnet of that GT in my head.

Last book you read?

In total? - probably when I read Michel Foucault’s History of Sexuality Pt. 1. However I read a lot of bits of books at the same time, so I read Lord of the Rings for example, when I can’t sleep, and I have an audiobook of The Stand by Stephen King that I occasionally dip into when I feel like it.

Do you like the smell of gasoline?

I mean, see my answer on Australians and cars, but goddamn yes I’m one of those gas huffing bitches who rolls down the window at service stations.

The last movie you saw?

For someone who studies film I’m currently not able to consume a lot of it - (when you’re studying something as closely as I am it’s sometimes hard to look at similar stuff without feeling overloaded?) so the most recent thing I watched was Mission Impossible Fallout. We bought the dvd around Christmas, thinking it would be a bankable ‘good shit film’, as I was a huge fan of the last 2-3 of the MI films, and oh my GOD WAS I DISAPPOINTED. The sexism! The shitty script! Oh god it was BAD. I wanted to break the dvd.

Do you have any obsessions right now?

Um.... perhaps you’ve heard of him.

Do you tend to hold grudges?

Oh boy and how. I’m the kind to remember exactly what someone said to me one time and hold it against their character forever. It’s a horrible trait but I secretly love it. I spot assholes at a thousand paces, that’s what 10 years spent working in bars/restaurants/cinemas/ record shops/cafes/anything public facing will give you. I can meet someone and instantly dislike them, so when that’s paired with them actually being a jerk to me, it’s like they’re on permanent ‘shit list’ in my mind. Terrible.

Are you in a relationship right now?

The ring on my finger says as much.

Tag:

I don’t usually tag followers because I know a lot of you like your privacy (totally understood) so instead of tagging them Imma tag @feedmeramyun @thotantics and @rosyyeols ❤️

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Avenue south residence price list

For over three decades I had been in the advertising and commercial film industry working with the talented, rich and famous. At the end of this, I thought I could disappear into quiet. I began my Madison Avenue advertising career in the heyday of advertising in the mid-60's, last century, at the top of the ad game, Young & Rubicam. Y&R had the top accounts, creativity and billing. It was a great place to work; if your family could initially afford to send you there (their starting salaries reflected their entry value). After a few restless years of changing departments four times we both (Y&R and I) finally realized corporate America was not the right fit for me and I went back to NYU film school and jumped to the other side: commercial film production. I was destined to keep working with the talented, rich and famous. Fate continued to linked me with some of the most talented commercial and feature film directors in the world; the likes of Ridley and Tony Scott and George Lucas. The Scott brothers and I, along with many multi-talented people, founded Fairbanks Films and that company took over the commercial film production advertising world in short order producing such famous TV commercials as the "1984 Apple Computer" spot that launched cyber technology into the world. Then the Lucas films people decided they wanted to get into the advertising game. And why not? After the motion film industry, the advertising business was making as much money as anybody. So over to Lucas I went with all the inventive, digital technology at hand. It's fair to say, we taught the Avenue south residence price list advertising world digital wizardry, even though others jumped on quickly. It was great fun being the director of marketing of the commercial division teaching the ad world how they could bring any image to the screen, if only they had enough money and time. We changed the look and abilities of commercial film forever producing thousands of spots worldwide. Many of these spots became household icons. During my three decades, I got to know the planet up close and personal and it was more than anyone could ask out of career! So I thought when it came time to retire I surely would be ready for peace and quiet. Wrong...

If you are in the film business, you get to know California really well. Or at least I thought I did. The weather, locations, studios and crews made California an almost MUST on any production schedule. Only strikes and cheap clients would prevent you from shooting in California. Fairbanks Films was my finishing school in southern California and the Lucas organization completed northern California. George Lucas preferred the north over the south (for reasons we won't get into).

While commuting to northern California from New York City my entire time with Industrial Light & Magic Commercials/Lucasfilms, I often took advantage of the natural wonders this part of the world has to offer. One of my most memorable trips was driving to the top of Mount Shasta, just south of the Oregon border. Mount Shasta is part of a dramatic volcano mountain range that snakes its way north. The size and grandeur of this mother of mountains was amazing; you could see it from 100 miles away. We had nothing like it on the East coast. And I thought enjoying its wondrous size and beauty was enough at the time. I would later learn otherwise... Ten years later I would return 'retired' for another purpose entirely...

Some say as we grow older and get closer to leaving, some become more spiritual, women become more masculine and men more feminine, or something like that. Well, anyway after some medical mishaps and 'enough is enough' syndrome, I did leave film and advertising. I mean what else was I going to do, produce another commercial? The last spot we did was the biggest commercial ever created for Ford motor company (90 days of shooting all over the world, the largest budget ever, aired all over the world; this was the perfect swan song. Did I need another cue? No! And there was this curious notion that something inside of me was awakening... Something else was next...

My mother was American Indian descended and my father Irish. My father's Celtic grandmother, my great grandmother, was a back woods Alabama healer. I call it my "I" and "I" links (Irish & Indian, both known for native healing). I remember sitting by great grandmother's bedside as a young child listening to her stories of her healing potions and how people would walk for days to get to her for "a healing."

She knew how to pick herbs from the forest floor and turn pine tree sap into a soothing medicine. So I imagined this ability was also in my DNA. And it was.

Filmmakers are often multi-faceted people and while I was working with one of my film directors on a project I developed a cold and shared my family's healing background. My director-friend immediately suggested that I see his alternative medical doctor named Dr. Herbert Fill. This filmmaker knew I was at the end of my film career and there was more to cure than a cold. Dr. Fill was a rare mix of psychiatry, acupuncture and homeopathic remedies, and commissioner of mental health in the city administration; all this in a Park Avenue office. It was not long before the patient became the student of alternative medicine under Dr. Fill. This was my transition from advertising into the "healing arts."

Once my transition, or should I say, my transformation began it went fairly quickly. After a couple of years of studying under Dr. Fill, I easily moved into energy therapy training called Reiki and Light Ascension; and became certified in these. These new alternative medical worlds introduced me to an entirely new community of people not associated with advertising or film. I began to know this was not going to be the beginning of a quiet retirement but a reinvention of self.

0 notes

Text

Henry’s

.bmc18-nav, .bmc18-nav--row, .bmc18-nav--item { display: block; font-family: sans-serif; line-height: 1em; } .bmc18-nav { margin-bottom: 1em; } .bmc18-banner--main { display: block; width: 100%; border-bottom: solid 0.25em #fff; } .bmc18-nav--item { text-align: center; padding: 0.5em; font-weight: bold; text-decoration: none; background-color: #ec3b9a; color: #fff; border-bottom: solid 0.25em #fff; transition-property: background-color; transition-duration: 0.2s; } .bmc18-nav--item:hover { background-color: #39b54a; color: #fff; } @media screen and (min-width: 480px) { .bmc18-nav { display: table; width: 100%; table-layout: fixed; } .bmc18-banner--main { /*border-bottom: solid 0.5em #fff;*/ } .bmc18-nav--row { display: table-row; } .bmc18-nav--item { display: table-cell; vertical-align: middle; border: solid 0.5em #fff; } .bmc18-nav--row > .bmc18-nav--item:first-child { border-left: 0; } .bmc18-nav--row > .bmc18-nav--item:last-child { border-right: 0; } }

Complete Listings Overview Learn More

Henry’s stores offer free classes on topics like vlogging and freezing motion (Photograph by Christie Vuong)

Gillian Stein started her journey to becoming CEO of Henry’s, her family business, when she was just six years old.

“One of my earliest memories of working in the store was spending Saturdays on the fourth floor of our building,” she says. “It was just a giant warehouse. I remember one time there was a misprint in a flyer, and I spent all day with my sister pulling flyers from the papers. We were covered head to toe in ink. When you grow up in a family business, you’re in it from birth!”

Henry’s—which was started in Toronto in 1909 by Stein’s great-grandfather—now has 30 locations and 400 employees across the country, but its continued success in a crowded market is due, in no small part, to an almost religious commitment to maintaining that local-store feel. Its employees may not be wandering around covered in ink, but they’re all passionate about the products they sell. That’s because there’s no one on the floor at any Henry’s who isn’t also a content creator themselves.

“They’re photographers, cinematographers, vloggers, YouTubers, Instagrammers . . . they’re part of the community they serve,” says Jeff Tate, Henry’s vice-president of marketing and e-commerce. “When you come into a [Henry’s] store, you’re going to talk to someone who’s probably going out to do their own shoot that weekend. They don’t want to just sell you gear—they want to help solve your particular creative problem.” Fostering personal, long-term connections with shoppers who share common interests is a point of pride.

“The way Henry’s looks at their customers is very different,” says Ryan Courson, store manager at Henry’s in Kitchener, Ont., and an equine photographer. “It’s not an environment where customers are numbers—[we don’t] just sell them whatever we can and move on to the next customer. It’s more about building relationships. The staff are all fellow photography and videography enthusiasts. There isn’t a staff member in the store who doesn’t have people come in and ask for them by name.”

One name every employee knows is Gillian’s. Stein meets regularly with staff from coast to coast in a program called Coffee with Company. Henry’s isn’t a one-store operation anymore—the company started expanding beyond its Toronto location in 1992—but Stein still wants to learn from the front-line workers, as if it were.

“It’s important to have a close relationship with employees,” she says. “I’ll ask them questions and tell them about things we’re thinking about. We’re always trying to get a better sense of what they see.”

Those eyes and ears on the ground have played a large part in Henry’s recent innovations. For one thing, “Canada’s greatest camera store” doesn’t actually think of itself as just a camera store—it’s a place for creators, especially digital ones who are making content for online consumption on an ever-expanding list of platforms, all of which come with their own particular gear challenges.

“That entry-level of the market where everybody needed a camera to take pictures on their vacation is gone,” says Tate, “but because of the internet, there are more content creators than ever before. Some people like watching gamers play video games on Twitch . . . well, great! Those gamers need a camera pointed at their face, and audio and lighting. If you’re a vlogger, you need something portable that picks up audio. We adapt to what people are making—this is the growth part of this industry.”

Henry’s product offerings have expanded to feed this booming customer base. Need a drone so you can film yourself from above skipping through a vineyard for your travel website? Done. Want a pretty backdrop for the picture of that lipstick you’re featuring on your blog this week? No problem. The company has sponsored several indie and influencer events and festivals, and is even catering to podcasters with a healthy selection of microphones and other audio tools. In some stores the area that used to feature printers is soon going to be devoted to this kind of equipment. The company is also working on a digital platform (details are hush-hush) that will help connect content creators with all the various services and people they need to help grow those side-hustle hobbies into main-hustle brands.

With this in mind, of course Henry’s has its own official in-house content creator, Gajan Tharmabalan, who spins the plates on all of the brand’s social media platforms. He makes content, of course, including how-to and product-review videos, but he also uses the channels to engage with Henry’s growing network of fans, and to promote the work of other photographers, filmmakers, You-Tubers and Instagrammers. This added focus on serving influencers means that Henry’s is not only nurturing customers who are much younger than the middle-aged male who, historically, is the camera-store client, but it is also attracting more women than ever. After all, female You-Tubers, vloggers and podcasters need gear, too.

“These new customers really didn’t have a home in terms of where to shop and get advice,” says Stein. “They all require unique solutions, and that’s really exciting for us.”

True to its roots, though, Henry’s is still a camera store, and it’s a place where you can actually touch and try the most expensive models on the market. At some key locations, including the Toronto store, there’s even a “shooting gallery,” where top-of-the-line equipment is rigged up for people to test. All stores offer free courses every week (Camera 101 is the most popular, but you can also sign up for bite-sized workshops on things like night photography or how to use freezing motion techniques).

The design of the stores has been changing, too, with an eye to becoming more welcoming to every type of customer. Gone are the intimidating, old-school L-shaped counters at the back of the store where a customer essentially had to walk the gauntlet of the entire shop before they could ask a question, and where all the product was under lock and key. The new Henry’s experience is airy and open, with an interactive wall playing videos or showing photography (something Tate calls “retail-tainment”), and the staff are roaming around, meeting their community, making sales and developing important career-long relationships with the content creators of the future.

a.bmc18-actionlink { display: block; text-align: center; padding: .8em; font-size: 1.2em; font-family: sans-serif; color: #fff; background-color: #EC3B9A; font-weight: 700; text-decoration: none; border-radius: 4px; transition-property: background-color; transition-duration: .2s } a.bmc18-actionlink:active, a.bmc18-actionlink:hover { background-color: #39b54a }

Even more of Canada’s Best Managed Companies » // API calls for recent posts to the 'best-managed-companies' tag. Grabs five of the given posts at random. NOTE: Post IDs are hard-coded below in `eligiblePosts` 'use strict'; var bodyClass = document.getElementsByTagName('body')[0].getAttribute('class'); var container = document.querySelector('#dynamicPosts'); // tag id for 'best-managed-companies' // var tagID = 351657; var postCount = 5; var exclude = parseInt(( bodyClass.indexOf('postid') >= 0 ? isolateID(bodyClass)[1] : 0)); var eligiblePosts = [1079843,1079845,1079849,1079851,1079853,1079855,1079857,1079859,1079861,1079863,1079865,1079867,1079869,1079873,1079875,1079877,1079879,1079881,1079885,1079887,1079889,1079891,1079893,1079895,1079897,1079899,1079901,1079903,1079905,1079907,1079909,1079911,1079913,1079915,1079917,1079919,1079921,1079925,1079923,1079927,1079929,1079931,1079933,1079935]; var chosenPosts = arrayRandomSubset(eligiblePosts, postCount, exclude); // subset of eligiblePosts, see function below var endpoint = 'http://www.canadianbusiness.com/wp-json/wp/v2/posts?'; endpoint += 'include=' + chosenPosts.join(','); endpoint += '&_embed'; fetch ( endpoint ) .then(function(response){ return response.json(); }) .then( function(data){ postsRender(data); }) .catch(function( err ){ console.log(err); }); function postsRender(data){ data.forEach(function(post){ // Define Post Elements // post container var thePost = document.createElement('div'); thePost.classList.add('row'); thePost.classList.add('bmc18-latest-post'); // visual holder var theVisual = document.createElement('div'); theVisual.classList.add('col-xs-12'); theVisual.classList.add('col-md-4'); // visual link var theImgLink = document.createElement('a'); theImgLink.setAttribute('href', post.link); theVisual.appendChild(theImgLink); // text holder var theText = document.createElement('div'); theText.classList.add('col-xs-12'); theText.classList.add('col-md-8'); theVisual.setAttribute('href', post.link); // the image var theImage = document.createElement('img'); theImage.setAttribute('src', post._embedded['wp:featuredmedia'][0].source_url); theImage.setAttribute('alt', post._embedded['wp:featuredmedia'][0].alt_text); theImgLink.appendChild(theImage); // the headline var theHed = document.createElement('h1'); theHed.innerHTML = '' + post.title.rendered + ''; theText.appendChild(theHed); // the dek var theDek = document.createElement('div'); theDek.innerHTML = post.excerpt.rendered; theText.appendChild(theDek); // the spacer var theDivider = document.createElement('hr'); //tack it all together thePost.appendChild(theVisual); thePost.appendChild(theText); container.appendChild(thePost); container.appendChild(theDivider); }); } // return the wordpress postID from the body class function isolateID( string ){ var pattern = /postid\-(\d+)?/; return string.match(pattern); } /** * From a given array, provide a subset * @param arr — the array from which to read the values * @param n — the number of results required * @param excl — a value to exclude from the results */ function arrayRandomSubset(arr, n, excl){ let out = []; // for the specified count, loop over the given array, select values randomly, and add them to the output array, but only if they aren’t already included. // NOTE: we temporarily increase the length of the loop to output an array of length n + 1. This is so that if there is an `excl` value provided for ( var i = 0; i < n + 1; i++ ){ // select a random position in the array let r = parseInt( Math.random() * arr.length ); // if the value at position `r` isn’t already in the output, add it if ( out.indexOf(arr[r]) < 0 ) { out.push(arr[r]); // if the value IS already in the output, decrement the loop to try again. } else { i--; } } // if the excluded value is not in the output, just trim to `n` results if ( out.indexOf(excl) < 0 ) { return out.splice(0, n); // if it IS in the output, remove it. } else { let e = out.splice(out.indexOf(excl), 1); return out; } }

The post Henry’s appeared first on Canadian Business - Your Source For Business News.

Are you looking for a Brain Injury Lawyer in The Greater Toronto Area?

Neinstein Personal Injury Lawyers is a leading Toronto injury law office. Our legal representatives feel it is their responsibility to help you to find the government and also health companies who can also assist you in your road to recuperation.

Neinstein Injury Attorneys has actually handled major accident claims throughout Greater Ontario for more than Fifty years. Its locations of proficiency include medical, legal, and insurance coverage concerns associated with healthcare negligence, car injuries, disability claims, slip and falls, product legal responsibility, insurance coverage disputes, plus more.

Neinstein Personal Injury Lawyers

1200 Bay St Suite 700, Toronto, ON M5R 2A5, Canada

MJ96+X3 Toronto, Ontario, Canada

neinstein.com

+1 416-920-4242

Visit Neinstein Personal Injury Lawyers https://neinstein.ca/about-us/ Connect with on Linkedin Follow Neinstein Personal Injury Lawyers on Instagram

Contact Sonia Nijjar at Neinstein Personal Injury Lawyers

Read More

#Neinstein Personal Injury Lawyers#Toronto Personal Injury Attorneys#Greg Neinstein#auto accident lawyers

0 notes

Photo

CINEMATOGRAPHY OSCAR NOMINEES ON AUTHENTICITY AND AVOIDING VFX https://ift.tt/2OZteQ0

The DoPs behind 1917, Joker, The Irishman, Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood and The Lighthouse reflect on the bold choices they made to bring dynamic visions to the screen.

Cinematographers are moving both forward and backward in technological terms this year, ironically in pursuit of the same goal: authenticity.

Avoiding VFX and instead opting to shoot reality has been a central theme. Robert Richardson used real Los Angeles backgrounds for the driving scenes in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood. Roger Deakins contended with real explosions and fires in Sam Mendes’s 1917.

Rigging equipment has also been a common talking point for DoPs in 2019. Deakins pushed the boundaries of stabilising devices to enable extended tracking shots for the continuous-take approach of 1917, while Papamichael explored the limits of large-format cameras, putting them in positions that would have been impossible a few years ago (on a low mounted arm attached to a racing car, in one case). Perhaps most complicated of all was Rodrigo Prieto’s “three-headed monster”, a three-camera set-up used to aid the CGI de-ageing process for Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman.

These and other top cinematographers no longer debate analogue versus digital, with plenty saying it is digital and film, rather than digital or film. This is in part due to rapid advances in camera technology by companies like Arri, with films including 1917 utilising a large-format digital camera that, according to Deakins, is as good as any film camera.

Mixing light sources has also been in vogue, with Lawrence Sher using harsh fluorescents and urban streetlamps to create the heightened eeriness of Joker and grittiness of the city.

Whether they are using old-school filmmaking techniques or the latest technology, these cinematographers are creating brave new worlds for audiences and their craft.

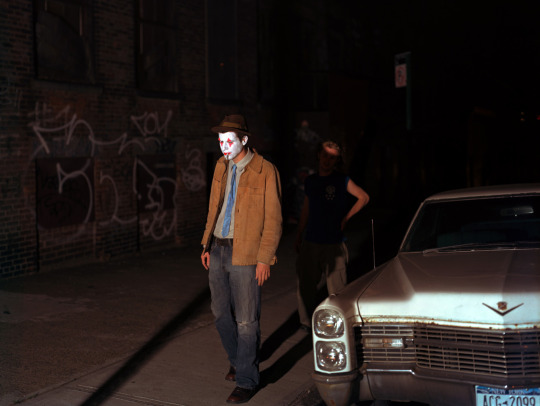

Lawrence Sher - Joker

SOURCE: NIKO TAVERNISE

LAWRENCE SHER ON THE ‘JOKER’ SET

Lawrence Sher has been known primarily for his work on comedies including Todd Phillips’ The Hangover trilogy, Paul, The Dictator and I Love You, Man, before he reunited with Phillips to create the dark, sinister world of Joker.

While Joaquin Phoenix’s performance threw up regular surprises during the shoot, Sher was a ready and willing partner for the award-winning actor, and says his own work plumbing the depths of the DC Comics arch villain — which won him Camerimage’s Golden Frog award in November — is not as big a departure as it initially appears.

What was the shooting schedule like for Joker?I read the script about a year before, did an early scout in March [2018] and then prepped for 10 weeks. The shoot lasted 60 days with one day of shooting lost due to issues with the LED lighting on the New York City subway sequence.

What was your approach to Joker’s colour scheme?My main colour palette was drawn first and foremost from real lighting fixtures that exist in the city. I also looked at movies of that era in which the movie takes place [1981], the colour of the film stock at the time and how it would capture all of this mixed light. The colour palette is a mix of utilitarian light and uncorrected fluorescents — we kept their crappy look so it wouldn’t be clean.

We changed out some of the streetlights so they would be sodium vapour, as opposed to LED which many streetlights are now. When we shot at dusk, you have that blueish light that mixes with the sodium vapours and suddenly you have the colours that I think people associate with the movie: the blues, greens, oranges and greys. You can see the messiness of the city.

How did you approach working with the actors to capture their performances?On set we maintain a certain rhythm for the actors. If they have to go back to trailer, even for 20 minutes, there is a momentum loss. So if I can shoot fast, they never have to leave the set. It helps everybody, especially the scene.

Todd Phillips encouraged improvisation, for instance the bathroom scene where Joker starts to dance after killing the men in the subway. Did that approach affect the shooting?That shot was improvisational. He was going to come into the bathroom, hide the gun, wash off the make-up and stand in the mirror and laugh. But with Todd, the movie is constantly being rewritten so you are discovering it as you make it. All of the planning is there but he’s always flexible. With that scene, he wanted to try it non-verbally. He played a piece of music — he didn’t tell the camera operator what was going to happen — and we got that scene in one take.

Was your approach to Joker different to your other films?My lighting approach is not any different. We are not servicing comedy [in Joker]. Some of the compositions come to the forefront perhaps, more than in my previous works. But my approach, particularly with Todd, is to allow for flexibility and freedom. A lot of it is co-ordination with production design and needing the freedom to be able to light a big space. To have the world lit as opposed to focused on a specific person on a mark.

Which sequence was the most challenging to shoot?The subway scene where he kills three Wall Street guys. We shot on a stage and with LED panels. It was challenging because while we had more money than other independent films, it’s still a budget issue. Todd had always described it as a fever dream — this kind of escalating light show. We accomplished it with a very expensive row of LED lights on both sides, though not too many LEDs because we tried to keep to the light as they had it in the 1970s and ’80s. I was taking the New York subway all the time and shooting with my iPhone to figure out the lighting for that scene.

How did you find working with Joaquin Phoenix?It was a transformative experience watching him act and getting to know him. I didn’t say anything to him during prep; he was a little bit intimidating. He apologised to me for acting weird and I said, “No man, do your thing.” We grew to have a good relationship, where we would challenge each other with the choices on set.

Rodrigo Prieto - The Irishman

SOURCE: NIKO TAVERNISE PICTURES

RODRIGO PRIETO WITH MARTIN SCORSESE ON THE SET OF ‘THE IRISHMAN’

Mexican cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto has worked alongside acclaimed directors including Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu (21 Grams, Babel), Ang Lee (Brokeback Mountain) and Pedro Almodovar (Broken Embraces). The Irishman marks his third feature with Martin Scorsese, after The Wolf Of Wall Street and Silence.

Prieto describes the epic crime drama as one of his most challenging projects to date: an intensive 108-day shoot involving more than 300 set-ups, with the added challenge of managing a complicated CGI de-ageing process for the main actors, which incorporated a “three-headed monster” camera rig.

Although Martin Scorsese is an avid supporter of shooting on film, you had to use digital as well to achieve the de-ageing technique.Yes, 56% was shot on digital and 44% on film. The overall look I thought had to be based on film negative because of the memory aspect. Scorsese talked about home movies, this sensation of remembering the past through images, so I developed looks based on still photography, Kodachrome and Ektachrome.

For the visual effects, it was necessary to shoot with digital cameras where the face had to be replaced with CGI. Visual-effects supervisor Pablo Helman from Industrial Light & Magic needed three cameras synched for every angle and the shutters had to all be in perfect sync. The challenge of getting three cameras to move in unison meant that using film cameras from a practical standpoint was nearly impossible.

Was it Pablo Helman who came up with the idea of using CGI to de-age the actors?Yes, when we were shooting Silence, Pablo said he thought there was a way to make actors look younger through computer-generated imagery. He came up with a three-headed rig where the central camera, the Red Helium, is capturing the shot and two witness cameras, Arri Alexa Minis, are sat on either side of the main camera to read the infrared map of the actors’ faces. We called it the “three-headed monster”.

Can you talk about the stages of the de-ageing process and how that was achieved?There are several different stages. Prosthetics were used to make the actors look older. Make-up could make the actors look younger, for example making a 70-year-old actor look like they were in their 50s. VFX and CGI de-ageing were used when the actors are close to the transition to make-up, and that was complicated as the ageing transition was subtle, say, only a few months in time rather than several years. The technical and make-up teams had to be sure the transition was smooth.

How did you map out the visual arc of a film that spans five decades over three-and-a-half hours?We did not want to make it over-stylised or flashy. Scorsese wanted the camera to reflect the way Frank Sheeran [played by Robert De Niro] approached his job, which was simple, methodical and repetitive. The audience sees the same shots with Frank — the camera pans around at the same angle. When we were with other characters, like crazy Joe Gallo, the camera behaves differently.

How did the fact the film was made to screen first and foremost on Netflix affect the way it was shot?For the most part it wasn’t a consideration. Scorsese designs his shots in a way that helps the story. The one thing we did change was the aspect ratio. Normally, Scorsese would use widescreen but in this case we thought we had better use 1.85 because it would fill up home screens. It also fit Frank’s personality more, as well as helping to show the height difference between the characters. Frank was a tall man so we made special shoes for De Niro and boxes with cushions where he sat. For accuracy, we also changed his eye colour to blue.

You were working on a tight schedule. Was there any room for improvisation during the shoot?When the actors want to try something different, Scorsese will almost always go for it. Near the end of the film, Frank is looking as his car is being washed and it’s a defining moment. We lit the scene for him standing and always looking at the car. Then De Niro said, “I always kind of imagined being inside the car.” So Marty said, “Oh, OK, let’s do that.” I had to set it up in three seconds. As soon as we shot it, I could see that his performance was there.

Jarin Blaschke - The Lighthouse

SOURCE: CHRIS REARDON

JARIN BLASCHKE ON THE SET OF ‘THE LIGHTHOUSE’

Born in the Los Angeles suburbs, Jarin Blaschke continues a collaboration with filmmaker Robert Eggers that began on the latter’s 2008 short The Tell-Tale Heart and encompassed his haunting 2015 feature debut The Witch. For The Lighthouse, the pair conjured up another strange and foreboding world: a mysterious New England island in the 1890s, inhabited by lighthouse keepers Robert Pattinson and Willem Dafoe. Blaschke deployed innovative lighting and lensing solutions to take on not just the wilds of authentic Nova Scotia locations, but the demands of dark, cramped, wet settings.

How many years did it take to develop the concept of The Lighthouse?I didn’t have a script until a month or two before prep, but Rob first pitched this idea probably three years before that. With him, it starts with atmosphere, so my subconscious was working on the atmosphere at the same time that we were developing The Witch. We didn’t know which one would go [first] and then The Witch happened.

The Lighthouse was shot in black and white, with a 1.19:1 aspect ratio, on Kodak Double X 35mm film format, which dates from the 1950s. How much testing did you do?There was a battery of tests I put myself through, like testing real oil lamps to see how to do it with an electrical lamp. I had to know how to light differently: I bolstered the light levels by 15, sometimes 20 times, and the film stock had to be tested in rain, backlit to know where it looks like night but also doesn’t look overly lit.

What logistical challenges did you face shooting on location in Nova Scotia?The weather was bad and added about four days to our schedule. It could have been worse but we had a covered set. We couldn’t do a night scene one night because it was too windy and even with day scenes, you have frames where you need to bounce light back using a giant sail and it gets a little hairy. There was a lot of eating cold porridge in the dark in the morning and the breakfast tent was going to blow away. We had to build this hardcore tent just to have breakfast. It adds to the movie, I hope.

In exploring the space between reality and insanity in The Lighthouse, did you use special lenses for certain scenes?I went to Panavision. I know vintage lenses are really trendy right now. I had some experience with the usual suspects: Cooke Series 2s and Super Baltars [used in The Godfather and The Birds]. They put original Baltars in front of me and I fell in love with them. So we had old Baltars from the 1930s. We used the first high-speed portrait lens of the 19th century for special shots, like [Robert Pattinson] having sex with a mermaid, the hand going down the body. Stuff that was super heightened where we could get away with it.

How did your collaboration with Eggers inspire you for certain images?I’ve known Rob for 12 years so I knew there were going to be a lot of symmetrical two-shots. There is one direct reference to a Sascha Schneider painting. And the last scene in the film is in the lookbook. Those are the only two references, everything else I tried to create. I know Rob watched all kinds of crazy stuff, like videos with shark genitals.

You are also working on Eggers’ next film, The Northman. What can you say about it?Rob says very little. It’s a bigger movie than the others. I can say it’s a Viking revenge movie and we are shooting in Europe. I think he feels a responsibility to do a trilogy. It’s dark and unusually violent.

Robert Richardson - Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood

SOURCE: ANDREW COOPER

ROBERT RICHARDSON WITH QUENTIN TARANTINO

A nine-time Oscar nominee and three-time winner, Robert Richardson’s career has been closely associated with three filmmakers: Oliver Stone, Martin Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino. For Stone, he photographed 11 features in a little over a decade, winning the Oscar for JFK; two of his five collaborations with Scorsese brought him Oscar statuettes (The Aviator and Hugo); and he shared Camerimage’s director and cinematographer duo award with Tarantino for their work across six films including Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood. Richardson is known across the industry for pushing boundaries and doing whatever it takes to achieve a shot.

How would you typify your relationship with Quentin Tarantino?A relationship with a director is a marriage. I have been fortunate enough to forge a series of relationships with all of the directors I’ve worked with from the beginning. It’s the idea that you are linked together and begin to understand how the other speaks, what you like and don’t like. It’s so important. Collaboration at that level is why rock ‘n’ roll bands are the very best when they hold out and play together as the same team as long as they can. The Beatles wouldn’t have been who they were without John, Paul, George and Ringo.

What is your creative process like with Tarantino once you’ve read the script?Quentin was in the room when I first read the [Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood] script. It took me a substantial time to read it. After we had dinner, we made notes and then he played music: ‘Good Thing’ from Paul Revere & The Raiders, ‘Mrs Robinson’ from Simon & Garfunkel, ‘California Dreamin’ from Jose Feliciano. The soundtrack is like a character in the film; it leads you, it is continuously playing from a radio station. The music helped build on the emotion of the characters and the movement of the film.

What is Tarantino’s process for selecting shots?He only shoots on film, he only processes on film and he only watches dailies on film. He doesn’t see digital replication until he gets to the Avid in the editing room. Our process is to shoot a film chemically, process and print chemically, and that print is duplicated on a 35mm projector. You then project the film as well as the digital intermediate, and they need to replicate each other perfectly, otherwise Quentin doesn’t want to discuss it. It’s definitely challenging, but that’s how we get to be better artists.

And when filming, Tarantino always sits beside the camera?Quentin is a director not a selector. He sits beside the camera. There is no video village, there is no video replay. You don’t go back and look at something. He watches the actors and their performance. If he’s got it, it’s over. If there is an error, something happened or an actor needs a retake, he will listen to why, but he will always choose in the editorial process the very best performance. The film is golden in its use of warm, saturated colours. We wanted to make a film that was about California and sunshine. On my side, it’s a combination of film stock, lenses and light. For the golden exteriors, we used a combination of Panavision’s anamorphic lenses and golden lenses.

You are known for using myriad film stocks to achieve different looks. What did you use for this film?We shot 35mm anamorphic, except when shooting Rick Dalton’s western television series, then we were 35mm black and white, and we shot with spherical zooms mostly in 1.33. There were also two sequences at Sharon Tate and Roman Polanski’s home that we shot on Kodak Ektachrome, one in 16mm black and white and the other on Super8mm colour.

Roger Deakins - 1917

SOURCE: FRANÇOIS DUHAMEL/UNIVERSAL PICTURES AND DREAMWORKS PICTURES

ROGER DEAKINS ON THE SET OF ‘1917’

Winner of four Baftas and an Oscar (secured last year for Blade Runner 2049 on his 14th nomination), the prolific Deakins has been an influential figure in cinematography since he burst on to the scene with 1984. On that film he pioneered a bleach bypass process to achieve a washed-out look that went on to be used in films including Se7en and Saving Private Ryan. He has also been at the forefront of embracing digital filming methods, not least on Sam Mendes’s Skyfall.

He reunites with Mendes on 1917, which follows two soldiers on a mission to avert a strategic disaster during the First World War. Deakins and Mendes had to invent new ways to move the camera to create the impression that the narrative was unfolding in a single, continuous shot — an innovative feat that puts the audience on the frontline.

How did you achieve so much fluidity in single camera shooting?We used a lot of different rigs. Probably 60% of the film was shot on a stabilised remote head. Some shots are done on the Trinity [Arri stabiliser rig], some are done on the conventional Steadicam and there’s even a drone. But the majority of the film is done remotely with a stabilised head that’s either carried by the grips or a tracking vehicle on the end of a crane or on a wire.

How did you plan such incredible camera movement while keeping up the illusion of one continuous shot?Sometimes it’s put on to a wire and then moved, or it’s taken off the wire and then someone carries it or runs with it so it all becomes one shot. The reason was not only to sustain the scene but also that we didn’t want to cut in some of the obvious places.